Mauro Bomba, La Sapienza University of Rome

Matteo Maiorano, La Sapienza University of Rome

Laura Valentini, La Sapienza University of Rome

Scientific supervision: Christian Ruggiero, Maria Romana Allegri, and Stefania Parisi

Publication date: December 2025

DOI: 10.25598/EurOMo/2025/IT

Report produced under the EC Grant Agreement LC-03617323 – EurOMo 2025, Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology Media Policy. The contents are the sole responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission. This report © 2025 by Euromedia Ownership Monitor (EurOMo) is licensed under CC BY 4.0

The Italian media system is dominated by a few large publishing groups controlling most of the country’s media outlets. Fininvest S.p.A. (Mediaset), Cairo Communication S.p.A. (RCS), Gedi Gruppo Editoriale S.p.A, and Tosinvest S.p.A together account for over 50% of the outlets included in this study. These actors – along with Rai Group S.p.A and Sky Group Limited, both concentrating its business solely on the television sector, own fewer outlets – represent about 40% of the total value of the SIC (Integrated Communications System) (AgCom, 2024), the index used by the national regulator AgCom to measure the sector’s overall market share. This indicates a media market concentrated in the hands of a few players who, while formally complying with antitrust limits, effectively exert dominant control over national information flows.

The leading figures of these major media groups often hold significant interests outside the publishing and information sectors. Notable examples include John Elkann, who through Exor NV controls GEDI along with investments in the automotive, financial, and healthcare industries; or Giampaolo Angelucci, whose Tosinvest S.p.a. combines media holdings with ventures in healthcare and real estate.

Since the 2023 edition, several developments have reshaped the Italian media landscape without altering its structural concentration around a few major players. After the death of founder Silvio Berlusconi in 2023, ownership of the Fininvest group was divided among his five heirs, while maintaining its formal unity. In the same period, Il Giornale was sold by the Berlusconi family to Angelucci’s Tosinvest Group through the transfer of Società Europea Edizioni. With this acquisition, Tosinvest brought together under one ownership the main right-wing newspapers in Italy, already owning Libero and Il Tempo.

Similar dynamics have affected GEDI, controlled by Exor, which began restructuring its assets by selling several local newspapers and the magazine L’Espresso (Pietrobelli, 2023). More recently, Exor has reportedly entered preliminary talks for the possible sale of its two main newspapers, la Repubblica and La Stampa (Reuters, 2025).

As for the public broadcaster Rai, its governance remains heavily influenced by political forces. Recent episodes have raised concerns about political pressure on its newsrooms, as reported both by the journalists’ union UsigRai (UsigRai, 2024) and by the European Commission (European Commission, 2024).

Finally, there is a growing interest among large media groups in digital-native news outlets. Within the sample analyzed, for example, Webboh and Freeda belong to the Fininvest group, while VDNews is owned by GEDI/Exor. This trend illustrates the intent of major operators to expand their influence toward new audiences and formats beyond traditional media.

The Italian media ownership system is notably complex. A consolidated pattern emerging from financial and ownership data is the so-called “Chinese box” structure, where a holding controls several subsidiaries — and ultimately media outlets — through a chain of sub-holdings. This layered system allows ultimate owners to retain control through their position atop the ownership pyramid, often without holding an absolute majority of shares, making it difficult to identify the actual beneficial owner behind each outlet.

Compared to the 2023 EurOMo Report, the chain of sub-holdings that characterizes the Italian media ownership system remains largely in place and, in some cases, has become even more complex. This is due to both the emergence of new players and to the reorganization of established ones. The death of Silvio Berlusconi in 2023, for instance, led to the redistribution of Fininvest shares among his five heirs – Piersilvio, Marina, Eleonora, Barbara, and Luigi – further complicating the ownership structure of the group.

Fig.1 – MediaForEurope before and after Silvio Berlusconi’s death

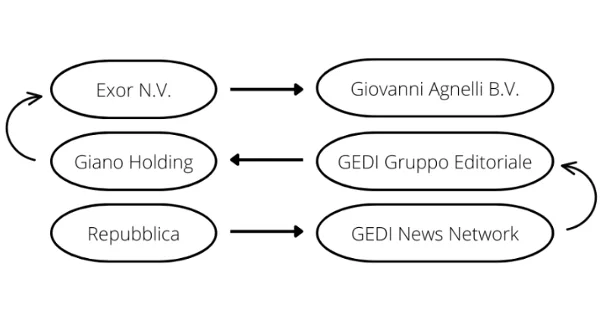

Exor NV group and the Agnelli family (one of the oldest and most powerful families of Italian entrepreneurs) represent another sample of the complexity of ownership chains in Italy. Exor indeed owns – in addition to the already mentioned Repubblica – other Italian newspapers and media outlets, such as La Stampa and Il Secolo XIX, through the same Gedi group. Some radio outlets (such as Radio Deejay and Radio Capital) and magazines (National Geographic, Limes) also belong to different editorial companies that Gedi ultimately owns.

Fig.2 – La Repubblica ownership’s chain

Many of the analysed ownership groups show relevant connections with foreign ownership: Exor owns The Economist Group, which publishes the British newspaper The Economist; Mediaset owns Mediaset España, and it also has relevant shares of the German ProSieben.Sat1 TV company and the Tunisian TV channel Nessma; through its parent company Unidad Editorial, RCS publishes El Mundo and Marca, two prominent Spanish sport newspapers.

As previously mentioned, another structural feature of the Italian media system, complementing the “Chinese box” ownership model and further complicating the reconstruction of ownership chains, is the persistence of what Hallin and Mancini (2004) define as impure publishing in which news outlets are owned by groups with significant business interests outside the information sector, such as automotive, finance, sports, real estate, or healthcare. This model of diversified and collateral interests creates links with non-media companies and raises questions about the extent to which external business activities may influence editorial independence. In the most prominent cases, such as Exor and Tosinvest, these interests are highly diversified.

Fig. 3 – Finanziaria Tosinvest: a case of impure publishing

Another example of non-media ownership is represented by Il Sole 24 Ore and Avvenire, owned respectively by Confindustria – the association of Italian entrepreneurs, a key player in the country’s economic and political system – and by the Italian Episcopal Conference (hereafter CEI), closely tied to the Vatican and the Catholic Church. Both newspapers thus reflect ownership structures with strong organizational and institutional affiliations outside the journalistic sphere.

Fig. 4 – Avvenire and Il Sole 24Ore, two cases of peculiar political and organizational ties

Political ties, while rarely made explicit, often emerge through editorial positioning. The most emblematic case is that of the Fininvest (Mediaset) group, historically linked to Silvio Berlusconi, who was both its main owner and political leader of the Forza Italia party. Similarly, Il Giornale has long been associated with Berlusconi and the center-right political ideology and continues to uphold similar editorial lines even after its acquisition by Tosinvest, chaired by Giampaolo Angelucci, son of Lega party (center-right) deputy Antonio Angelucci. The same logic applies to the public broadcaster Rai, whose news programming is strongly but shaped by political influence. A comparable case is Il Fatto Quotidiano, known for its proximity to the Movimento 5 Stelle party.

Compared to the 2023 edition, several issues persist regarding the economic and financial transparency of media companies. Financial statements and corporate filings are generally aggregated at the company level, making it difficult to isolate data for individual outlets or sectors. Information on the composition of editorial staff is often missing, and when available, it is usually presented in aggregate form rather than broken down by outlet or function (for example, the number of employed journalists is reported for Rai S.p.A. but not for individual channels such as Rai1, Rai2, or Rai3).

Access to corporate documents, as will be discussed in greater detail below, is often costly, since financial reports are available only upon payment of a fee, and particularly complex for larger media companies. Their “Chinese box” ownership structures, in which control is exercised through chains of holding and subsidiary companies, make it difficult to identify the ultimate beneficial owners. While the identity of the main ownership families and groups (such as Mediaset, GEDI, and RCS) is publicly known in Italy, formal verification requires access to fragmented information dispersed across multiple corporate entities and restricted registries. Moreover, the ability to distribute advertising revenues across several companies within the same group allows firms to remain below the concentration thresholds established by the Sistema Integrato delle Comunicazioni (SIC).

Additional information often missing from financial reports concerns public funding and institutional advertising. Despite legal disclosure requirements (Law 124/2007), these data can only be retrieved from public databases that are difficult to access and navigate. While citizens can consult open data published by government sources such as the Department for Information and Publishing, transparency remains uneven: direct public funding is relatively traceable, but indirect forms are not. For example, companies must report revenues from institutional advertising to AgCom, yet the Authority does not make these figures public or accessible. Furthermore, when such information is included in financial statements, it is typically presented only in aggregate form, preventing any clear identification of funds allocated to advertising or other forms of public support.

Finally, in the field of social-native information outlets, disclosure requirements remain highly inconsistent. Obligations to file company information with the company register (Registro delle Imprese), the Registro degli Operatori della Comunicazione(hereafter ROC), or local courts vary considerably, resulting in non-homogeneous transparency standards compared to traditional media and limited traceability of ownership, partnerships, and funding sources.

The main risks to transparency in Italy stem from complex ownership chains, the lack of detailed data in corporate financial statements, making information traceability difficult, and a convoluted funding system that remains largely opaque to citizens.

Additional challenges concern transparency in institutional advertising and indirect public funding. Although specific laws require disclosure in company accounts and institutional databases record this information, these data remain difficult to access and interpret.

Another critical factor, widely discussed in academic literature, is the close proximity between media owners, publishers, and political parties or interest groups, also within public broadcasting. Some of the most significant cases have already been mentioned: the political partitioning of influence within Rai and the resulting editorial pressure; the presence of ownership families with prominent political roles; the marked ideological positioning of several newspapers; and the existence of publishers directly linked to major civic stakeholders such as the Catholic Church or business associations. These relationships are often obvious but not acknowledged, especially to observers outside the Italian context.

The strong presence of economic interests in non-media sectors, combined with widespread cross-ownership and relatively weak limits on market dominance, increases the risk of conflicts of interest and pressures on editorial independence, undermining the transparency and traceability of ownership, interests, and corporate operations.

Finally, another critical issue concerns the structural fragility of the Italian media market, certified by Paolo Mancini (2002) over twenty years ago, which has led to growing instability in ownership structures among major publishing groups. In recent years, numerous acquisitions and mergers have progressively reshaped the national media landscape. In 2016, Cairo Communication acquired RCS from Exor NV – the Agnelli family’s holding – which later purchased GEDI and began downsizing by selling several local outlets and the historic magazine L’Espresso, while reportedly considering the sale of its flagship newspapers la Repubblica and La Stampa. At the same time, Tosinvest acquired Il Giornale from the Berlusconi family, which subsequently initiated a reorganization of the Fininvest holdings following the death of founder Silvio Berlusconi. These developments reflect, on one hand, the structural weaknesses of the sector, exacerbated by difficult public subsidies (Il Post, 2025) and, on the other, a persistent concentration of control within a small number of dominant players, despite apparent movement in ownership structures.

Looking at the “top-down” distribution, sources such as the Censis 2024 Report on Communication (Censis 2024) and the Digital News Report 2024 – Italy edition (Cornia 2024), highlight how television is still the population’s preferred medium for accessing news, followed by online information sources, which include both linear (newspaper websites) and non-linear (original pages operating on social media) sources. However, the latter are preferred by Italians: The Censis report, for example, sees them used by 85% of users, while online newspapers (linear) are at 30.5%. Print media, on the other hand, ranks increasingly lower in the rankings for both sources mentioned.

As for non-linear media distributors, the Digital News Report (2024) cites social media (22%) as an increasingly important source for online news, followed by search engines (20%) and aggregators (9%). The Meta platforms, Facebook and Instagram, top the rankings with 65% and 54% of loyal users respectively, followed by YouTube in second place with 58%; TikTok closes the list with 25% and X with 10%.

The most significant risk in terms of distribution pertains to non-linear distributed content. While traditional media and online newspapers have dedicated entities and agencies established to monitor them (auditel.it for TV, ads.it for print media, editoriradiofoniciassociati.it for radio, audiweb.it for online newspapers), the same openness to the public does not exist with regard to social media, either for outlets’ social media profiles or for born-digital media and influencers pursuing journalistic activities, that are often not recognized as journalism since they are carried out by unregistered publications or by individuals who are not members of the Order of Journalists. In this respect, the problem is twofold: on one hand, there are no standard monitoring indicators concerning the good health of a social media-born outlet; on the other hand, this type of activity is often confined within the internal departments of publishing houses (or within the Insights sections of influencer profiles), or outsourced to external companies that provide this data only upon agreement from the client, or in any case upon payment of considerable fees. This leads to a lack of availability or partiality of information on the relevance of individual outlets considered in the social media sample.

Data concerning dissemination via digital platforms is very clear on one side (number of likes, number of followers available on single pages) but opaque on the other. In fact, the phenomenon of buying and selling followers and “likes” is now well established and proven to be particularly problematic, on which national legislation has not yet shown clear signs of intervention. In addition to this, it should be considered that the number of followers does not necessarily correspond to the “market share” of the individual outlet, which must be monitored through statistics that are not publicly available.

Ownership transparency in the media sector is primarily governed by general legislation regulating ownership disclosure and market stability for companies operating in Italy. The Civil Code (Art. 2435) requires companies to prepare and file their annual financial statements with the Company Register (Registro delle Imprese), the main public registry used to identify a company’s legal ownership and corporate structure. Established by Law No. 580/1993, the Register ensures the public availability of corporate and ownership data.

Media companies and journalistic outlets are subject to even stricter transparency obligations. Law No. 47/1948 requires newspapers and periodicals to be registered with the local court, including the identification of the editor-in-chief and the publisher. Law No. 416/1981, integrated by Law No. 650/1996, obliges print outlets to publish annually the financial statements of their controlling company on their own publications and to notify the relevant authorities of information concerning shareholders, financiers, and any transfer of ownership shares, thereby strengthening transparency safeguards in the sector.

The Consolidated Law on Audiovisual Media Services (Testo Unico dei Servizi di Media Audiovisivi – hereafter TUSMA, Legislative Decree No. 208/2021), which transposes EU Directive 2018/1808, extends these transparency principles to the audiovisual sector, including television, radio, online services, and video-sharing platforms. The TUSMA requires the publication of information on both direct and indirect ownership of media, assigning oversight responsibilities to the national regulatory authority for the sector (Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni – hereafter AgCom) through the registration of media companies in the Register of Communication Operators (Registro degli Operatori della Comunicazione – hereafter ROC), established by Law 249/1997 and implemented by AgCom Decision 66/08/CONS and subsequent amendments. The ROC thus becomes the central tool for collecting data on the corporate structures of communication operators.

An additional transparency instrument is provided by Legislative Decree No. 231/2007, as amended by Legislative Decrees No. 90/2017 and 125/2019, implementing the EU Anti-Money Laundering Directives (AMLD). This framework introduces the notion of the beneficial owner and establishes a dedicated register. Decree No. 55/2022 regulated its implementation, making the Register of Beneficial Owners operational within the Chambers of Commerce. The register collects data on the ultimate ownership of companies. Although subject to appeals and temporary suspensions regarding public access (2023–2024), it represents an important tool for ownership traceability and transparency, including for media companies and service providers.

In recent years, lawmakers have extended transparency obligations to digital operators as well. Article 1 of Law No. 178/2020, implementing EU Regulation 2019/1150, assigns AgCom supervisory powers over online intermediation services and search engines, requiring their registration in the ROC and the disclosure of essential information about their activities.

The transposition of EU media legislation in Italy has evolved through a progressive regulatory trajectory. In 2005, the first version of the Consolidated Law on Audiovisual and Radio Media Services (Testo Unico della Radiotelevisione – hereafter TUSMAR, Legislative Decree No. 177/2005) coordinated and implemented the main EU directives on broadcasting, starting from the “Television without Frontiers” Directive (89/552/EEC) and its subsequent amendments, providing Italy’s first unified framework for the regulation of the broadcasting sector. The text was later amended to implement further EU directives on audiovisual media services, culminating in the current TUSMA (Legislative Decree No. 208/2021), which transposed the provisions of Directive (EU) 2018/1808 (AVMSD).

Regarding media ownership transparency, the matter is mainly regulated by the provisions of EU Directive 2018/1808 (AVMSD), which were fully transposed into Italian law through the TUSMA. This framework complements other national laws, such as Article 2435 of the Italian Civil Code (1942) – which requires every Italian company, or any foreign company headquartered in Italy, to file its annual financial statements and list of shareholders with the Business Register (Registro delle Imprese) – and, specifically for the media sector, Law No. 47/1948, which further requires the identification of the editor-in-chief and owners, as well as the registration of newspaper titles with the competent local court.

It should be noted that the implementation of EU Directive 2018/1808 in Italy occurred with significant delay, leading to the opening of an infringement procedure by the European Commission in November 2020 and a subsequent warning in 2021 (European Commission, 2020, 2021).

The introduction of the European Media Freedom Act (EU 2024/1083 – EMFA) establishes common EU-wide standards for ownership transparency through the creation of a European Database on Media Ownership, ensuring interoperability among national databases. In the Italian context, the implementation of this regulation strengthens the role of AgCom as the National Regulatory Authority (NRA) and expands its mandate on transparency and pluralism by integrating it into the new European Board for Media Services. Moreover, the regulation requires Member States to entrust national authorities with maintaining accessible and up-to-date databases on media ownership. In Italy, this may necessitate harmonization of the ROC to improve accessibility, interoperability, and alignment with EU standards.

In parallel, the new EU Anti-Money Laundering Package – comprising EU Directive 2024/1640 (AMLD6) and EU Regulation 2024/1624 (AMLR4) – further reinforces transparency obligations and mandates interoperability of beneficial ownership registers at the European level. As for digital platforms, in line with the Digital Services Act (EU 2022/2065), Italy has designated AgCom as the Digital Services Coordinator, granting it new supervisory and reporting powers over online platforms.

Among the main risks to media ownership transparency in Italy, the most significant remains the general lack of accessibility of information. Data on the ownership structures of media companies are stored across several registries but are often difficult for citizens to access. The ROC, for instance, is publicly available but provides only basic company contact information; the Company Register, where financial statements and corporate changes are filed, can be consulted only upon payment of a fee — the research team that authored this report had to purchase multiple records, each costing approximately €10. Finally, the Register of Beneficial Owners, established in 2022, is currently inaccessible to the public following legal appeals that suspended its operation pending a ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union.

This challenge is compounded by the complexity of corporate structures in the Italian media sector, which, as discussed above, makes it difficult to identify ultimate owners and corporate interests. In addition, the widespread phenomenon of “impure publishers” — companies whose primary interests lie outside the media sector — increases the risk of interference with editorial independence and reinforces the need to remove barriers to ownership transparency and disclosure of collateral interests. Transparency regarding public funding also remains limited: data disclosed under Law No. 124/2017 are aggregated and do not allow for distinctions between institutional advertising and other forms of public support.

Another emerging risk concerns the regulation of accounts acting as information providers on VLOP platforms. These entities often operate through highly heterogeneous corporate and editorial structures that do not always fall within the definition of “media service providers” established by TUSMA. They are therefore not always required to register with the ROC or to be officially listed as journalistic outlets in local courts. This creates an asymmetry between the transparency obligations imposed on traditional publishers — who are subject to clear corporate disclosure rules—and those applicable to platform-based information accounts, which are bound only by general legislation.

As for the regulation of digital intermediaries, Italian lawmakers generally limit their interventions to the transposition of European directives—such as Law No. 73/2003, implementing Directive 2000/31/EC on electronic commerce—or to the publication of non-binding guidelines, such as those concerning par condicio online during election campaigns (AgCom, 2018). The Digital Services Act (Regulation (EU) 2022/2065), while requiring platforms to increase transparency in their processes and content management, does not impose any obligation to disclose ownership structures, which currently remain those established by Law No. 178/2020 implementing EU Regulation 2019/1150.

Another critical issue concerns the monitoring and sanctioning powers of the regulatory authority AgCom, which, though broad, are fragmented across multiple sectors and levels of authority and have limited deterrent effect. Ownership concentration thresholds in the media market remain high, monitoring procedures are complex, and infringement cases are often slow and resolved through warnings rather than sanctions. In this regard, Article 51 of the TUSMA – which sets out the limits within which communication companies must operate to safeguard pluralism and prevent excessive market concentration – does not establish fixed legal thresholds. Instead, it identifies “indicators symptomatic of a significant market power potentially detrimental to pluralism” (TUSMA, Art. 51, para. 3), mainly referring to revenue and turnover levels; for instance, these must not exceed 20% of the Integrated Communication System (SIC).

Finally, it is important to note that the Italian media landscape continues to suffer from structural weaknesses affecting both freedom and transparency. The 2024 Reporters Sans Frontières World Press Freedom Index ranks Italy 46th worldwide, highlighting a climate of threats to journalism, reduced editorial independence, the use of abusive defamation lawsuits (querele temerarie), and political pressure at the top of RAI. In July 2024, the European Commission also raised concerns about the politicization of the Italian public broadcaster and called for stronger guarantees of editorial autonomy. More recently, both the Media Freedom Report 2025 (Liberties, 2025) and the Media Pluralism Monitor 2025 (Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom, 2025) have pointed to persistent weaknesses in the governance and independence of public service media, noting political interference, poor transparency in RAI’s management, and limited disclosure of media ownership and potential conflicts of interest across the sector. In light of these findings, Italy is considered at serious risk of an infringement procedure for violation of the Media Freedom Act (Amendola, 2025).

AgCom (Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni / Authority for Communications Guarantees). (2018, February 1). Linee guida per la parità di accesso alle piattaforme online durante la campagna elettorale per le elezioni politiche 2018 [Guidelines for equal access to online platforms during the 2018 general election campaign]. https://www.agcom.it/documents/10179/9478149/Documento+generico+01-02-2018/45429524-3f31-4195-bf46-4f2863af0ff6?version=1.0

AgCom (Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni / Authority for Communications Guarantees). (2024, December 19). Sistema integrato delle comunicazioni. Risultati del processo di accertamento 2022 [Integrated Communications System. Results of the 2022 assessment process]. https://www.agcom.it/sites/default/files/media/allegato/2024/Allegato%20A%20Delibera%20502_24_CONS%20Chiusura%20SIC%202022_sito_0.pdf

Amendola, G. (2025, August 7). Rai, le opposizioni: “A rischio procedura d’infrazione Ue per violazione del Media Freedom Act” [Rai, the opposition: “EU infringement procedure at risk for violation of the Media Freedom Act”]. la Repubblica. https://www.repubblica.it/politica/2025/08/07/news/rai_opposizioni_infrazione_media_freedom_act_norme_ue-424777396/

Censis. (2024). Sintesi 34 – Rapporto annuale sullo stato del Paese [34th Summary – Annual Report on the State of the Country]. https://www.censis.it/sites/default/files/downloads/Sintesi_34.pdf

Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF). (2025). Media Pluralism Monitor 2025 – Country profile: Italy. European University Institute. https://cmpf.eui.eu/country/italy/

Cornia, A. (2024). Italy – Digital News Report 2024. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2024/italy

European Commission. (2024, July 24). 2024 Rule of Law Report – Country chapter on the rule of law situation in Italy. https://www.eunews.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Country-report_Italy.pdf

Hallin, D. C., & Mancini, P. (2004). Comparing media systems: Three models of media and politics. Cambridge University Press.

Il Post. (2025, October 10). I giornali che ricevono i contributi pubblici (Prima rata 2024) [The newspapers receiving public funding (First installment 2024)]. https://www.ilpost.it/2025/10/10/contributi-pubblici-giornali-prima-rata-2024/

Liberties. (2025, April 24). Media Freedom Report 2025 – Fourth annual report on media freedom in the EU. https://interaliaproject.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Liberties_Media_Freedom_Report_2025.pdf

Mancini, P. (2002). Il sistema fragile. I mass media in Italia tra politica e mercato [The fragile system. The mass media in Italy between politics and the market]. Carocci.

Mastandrea, G., Melis, M., & Di Natale, R. M. (2022, April 2). Dove i giornali sono un ricordo [Where newspapers are a memory]. L’Essenziale. https://www.internazionale.it/essenziale/notizie/angelo-mastrandrea/2022/04/12/distribuzione-giornali

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Eddy, K., & Nielsen, R. K. (2024). Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2024. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2024-06/RISJ_DNR_2024_Digital_v10%20lr.pdf

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., & Robertson, C. T. et al. (2025). Digital News Report 2025. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/digital-news-report/2025/italy

Pietrobelli, G. (2023, October 23). Gedi completa la dismissione dei locali – La cessione dei quotidiani nordestini [Gedi completes the sale of local papers – Transfer of northeastern newspapers]. Il Fatto Quotidiano. https://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2023/10/23/gedi-definitiva-la-cessione-di-sei-quotidiani-del-nordest-alla-cordata-guidata-da-enrico-marchi-finint-ecco-numeri-e-dettagli-delloperazione/7332052/

Reporters Sans Frontières. (2024). 2024 World Press Freedom Index – Journalism under political pressure. https://rsf.org/en/2024-world-press-freedom-index-journalism-under-political-pressure

Reuters. (2025, July 4). Italy’s Agnelli family approached by suitors for La Repubblica’s publisher. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/en/italys-agnelli-family-approached-by-suitors-la-repubblicas-publisher-2025-07-04/

USIGRAI. (2024, August 11). Usigrai: Copertura del territorio Tgr Puglia e ufficio RAI di Lecce, esigenze editoriali o politiche? [Usigrai: Coverage of Tgr Puglia and RAI office in Lecce, editorial or political needs?]. https://www.usigrai.it/usigrai-copertura-del-territorio-tgr-puglia-e-ufficio-rai-di-lecce-esigenze-editoriali-o-politiche/